Patients

-

- Angiography

- Angioplasty and Stenting

- Aortic Aneurysms

- Biliary Drainage and Stenting

- Carotid Artery Stenting

- Central Venous Access

- Colonic Stenting

- Fibroids

- Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage

- Gastrostomy

- Hepatic Malignancies

- Kidney Tumour Ablation

- Minimally Invasive Treatments for Vascular Disease

- Nephrostomy

- Oesophageal Stents

- Pelvic Venous Congestion Syndrome

- Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy

- Prostate Artery Embolisation PAE

- Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations

- PAE Patient Information Leaflet

- Ureteric Stenting

- Varicoceles

- Varicose Veins

- Vascular Malformations

- Vertebral Compression Fractures

- Vertebroplasty and Kyphoplasty

Patient Experiences of Interventional Radiology

Here you can see how Interventional Radiology or 'Image guided surgery' has benefited patients.

Contents |

If only I’d found out earlier I had pelvic congestion syndrome - BBC News

If only I’d found out earlier I had pelvic congestion syndrome - BBC News

IMAGE SOURCE,SOPHIE ROBEHMED

IMAGE SOURCE,SOPHIE ROBEHMED

Sophie Robehmed spent most of 2018 with chronic abdominal and lower back pain, symptoms she'd had before but never for more than a week or so. Then she was diagnosed with pelvic congestion syndrome - a condition no doctor had mentioned in the many years she'd been seeking medical help.

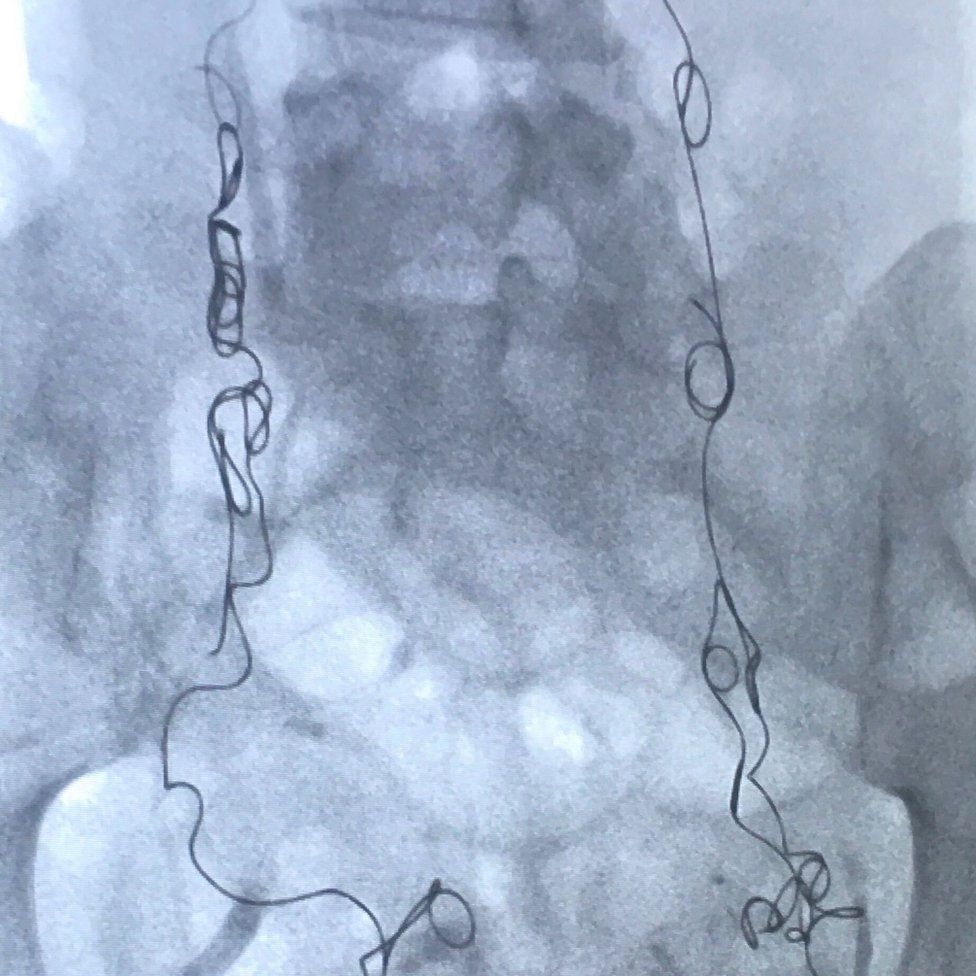

It's Tuesday 14 August 2018 and I am sedated, lying on an operating table, while metal coils are being inserted into my ovarian and pelvic veins via a catheter in my neck.

I have recently been diagnosed with pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS), or ovarian vein reflux as it's also known, a condition that can cause pelvic and ovarian veins to pool with blood, enlarge and press against surrounding organs.

This can cause, or exacerbate, a host of problems - irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), painful periods, backache and fatigue, to name a few - and often brings relentless pelvic pain.

There is no guarantee that the procedure I'm undergoing, known as a vein embolisation, will work. But I've been told that in about 80% of cases it succeeds in reducing or eliminating symptoms altogether, so it feels like my best hope after months of pain.

I began having painful, heavy periods and IBS-type symptoms in my teens, but it wasn't until I was in my 30s that pelvic congestion syndrome was mentioned as a possible cause.

In my early 20s, I was told that I probably had endometriosis, an often agonising condition that is caused by womb lining growing outside the uterus.

A gynaecologist told me the only definitive way to determine whether I had the condition would be to have a laparoscopy, in which a small camera is inserted via a small incision in the abdomen. Alternatively, I could try taking the pill.

As the laparoscopy felt like a drastic and invasive option at the time, I decided to try the pill.

It definitely helped to reduce the severity of my symptoms, and I am still taking it today - but it has never completely solved the problem, so I have undergone numerous investigations over the years.

I've had myriad scans: CT, MRI, transvaginal ultrasound.

I have been tested for food intolerances, and I've tried elimination diets.

I even had tiny cameras poked down my oesophagus and into my colon on the same afternoon.

When I had a flare-up, I was usually in pain for up to a week at a time, but towards the end of January 2018, I had a new experience.

IMAGE SOURCE,SOPHIE ROBEHMED

IMAGE SOURCE,SOPHIE ROBEHMED

This time, it began gradually with dull abdominal and lower back pain over a period of days that worsened until I was hit with the familiar aggressive cramps in my stomach and lower back.

In between being bent over in bed and going to the toilet, I was also sick.

A persistent dull ache followed the flare-up - but this time, it didn't go away.

I was signed off work and given oral morphine. A blood test also revealed a high level of inflammation in my body but it wasn't clear why; a GP thought I was probably fighting an infection.

A lot more uncertainty followed. I had many appointments and was given a lot of prescription drugs - and on occasions, antibiotics for suspected urinary tract infections.

I often dragged myself into the office, pained and worn out.

Then, in June 2018, I finally had the laparoscopy that I had decided against eight years earlier.

What is PCS?

Pelvic congestion syndrome (PCS) is a term to describe varicose veins in the pelvis area and can lead to chronic pelvic pain in women.

The pain is thought to be due to the varicose veins surrounding and pressing on the ovaries and sometimes the bladder and rectum. Women may experience a dragging sensation in the pelvis and a feeling of fullness in the legs. Women may also notice changes in their urinary and bowel habits, including a worsening of existing stress incontinence or irritable bowel syndrome symptoms.

There are medicines available for women, which can reduce pain and the size of the varicose veins. If this does not work, pelvic vein embolisation is an option, in which veins can be sealed and blocked.

Prof Andrew Horne, Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

When I came around from it, my gynaecologist told me that there was no sign of endometriosis but that I did have congested veins.

My latest transvaginal ultrasound report had queried "pelvic congestion" for the first time and my gynaecologist had now seen evidence of this for himself, but he didn't seem convinced that these veins could cause the level of pain I had been experiencing.

Still, he offered me a referral to a vein expert - Dr Aidan Shaw, a consultant interventional radiologist.

He went on to confirm that I had pelvic congestion in my left and right ovarian veins and in branches of another vein in my pelvis, the iliac vein.

While PCS remains a relatively niche diagnosis, the symptoms it can cause are common.

"Chronic pelvic pain makes up to 10-40% of gynaecological outpatient department referrals but it is not known what portion can be attributed to pelvic congestion syndrome," says Prof Andrew Horne, consultant gynaecologist and spokesperson for the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

"More research is required into this gynaecological condition, with awareness currently lacking."

Aidan Shaw, my former consultant, says some doctors are unfamiliar with pelvic congestion syndrome, and others are sceptical about its existence.

"PCS can present as a multitude of symptoms and signs that I think are often ignored or misdiagnosed by doctors and nurses," he says.

"It takes a clinician to think and believe in the diagnosis, and there are some who do not believe in the condition, sadly."

PCS and pregnancy

PCS is more common in women who have had at least one pregnancy because this increases blood flow to the pelvic area, and ovarian veins can be compressed as the womb expands. Either of these things can cause valves in the veins to stop working, and blood to flow backwards, leading to PCS.

Other causes include vein obstruction or the absence of vein valves altogether.

Although less common, men may have a version of PCS, diagnosed through visibly enlarged veins in the scrotum, known as varicoceles.

As an interventional radiologist, Aidan Shaw uses a variety of medical imaging techniques to diagnose problems, and then treats them using minimally invasive procedures. He says he and his colleagues are constantly trying to increase public awareness of what they can do.

"The only way is education - for doctors, the public, publications - and persistence," he says.

The embolisation I had in August 2018 blocked my congested veins with metal coils so that they could no longer fill with blood, enlarge, and cause me pain.

Since then, my symptoms have greatly improved, but I can still have nasty period pains. In January 2020, they were worse than usual, and I was given an MRI scan to check for adenomyosis, which causes the uterus's inner lining to break through its muscle wall, and can also lead to congested veins.

IMAGE SOURCE,SOPHIE ROBEHMED

IMAGE SOURCE,SOPHIE ROBEHMED

Thankfully, there was no sign of this condition - or any evidence of new congested veins either.

During my follow-up telephone consultation, I asked my gynaecologist whether she thought my pain and irritable bowel symptoms over the years could all have stemmed from PCS and bad periods, or whether there might have been another problem too. After more than a decade of medical tests, I craved clarity about the state of my own body from the voice at the end of the phone - but she told me that she couldn't answer my questions with any real certainty.

It wasn't what I wanted to hear but, more than a year since that conversation, and nearly three since the embolisation, I'm doing well. I feel lucky that I finally got diagnosed and was treated successfully, and I will forever be grateful to those little metal coils that have made a profound difference to my life.

Leading research at the Lister helps keep renal patients dialysing well - a patient's story

David Robinson, a 67 year old retired butcher who has lived and worked in Bedford all of his life, saw things change for him significantly in the summer of 2015. That is when he was referred by his local diabetes team to the renal service at the Lister hospital in Stevenage.

They discovered that his underlying medical conditions – diabetes and cardiac disease – had led him to experience progressive renal failure, which if left untreated would have threatened his life. In preparation for David to move on to haemodialysis, the Trust’s vascular surgery team created what is called an arterio-venous fistula – a connection between an artery and vein – in his left upper arm to allow his veins to develop so that the needles necessary to support long-term dialysis could be inserted.

Whilst under the care of the renal team, David was admitted to the Lister with a severe chest infection that turned out to be pneumonia. During this two-week stay in hospital, it became clear to his doctors that he needed to move on to dialysis quickly.

David takes up the story:

“I’ve had diabetes for a while now and generally speaking I’ve managed to do okay and lead as normal a life as possible. But back in 2013 I began to get swelling, particularly in my right leg. On one occasion when I was admitted to my local hospital here in Bedford, 13 litres of fluid was drained off.

“I felt okay at the time, but my leg continued to swell and I had to wear surgical stockings to help with that. There was also no apparent reason why the swelling was happening. But after a while, my diabetes team began to worry that it could be linked to kidney disease and they referred me to the Lister, where I was reviewed by one of its consultants.

“It was then that I discovered that despite feeling fine, my kidneys were not working. In fact I had what was called progressive kidney disease, which meant that unless something was done about that, the condition would just get worse and could threaten my life.

“The recommended treatment was dialysis and I opted for haemodialysis, which involves removing excess fluid, salt and wastes from the blood – effectively doing the job done by my kidneys. I had the procedure done to have a fistula created in my arm, but events overtook me when I was admitted to hospital in April 2016 with pneumonia.

“It took two weeks to recover from that and the renal team told me that I needed to start on haemodialysis right away.”

Whilst fistulas are the most effective means of supporting high quality haemodialysis, they can suffer problems – such as blood clots linked to a narrowing of the vein being used. Left untreated, the quality of dialysis reduces and the fistula can become unusable.

Spotting problems and addressing them early ensures that the fistula continues to be used and the patient experiences good quality dialysis. At the Lister, the renal team works with interventional radiologists to treat fistulas that have become compromised.

Narrowing of the vein – which is called a stenosis – is now treated using a technique called a fistuloplasty or venoplasty. During the procedure, the patient has a local anaesthetic to numb the area and sedation, if required. A small tube called a sheath, which is around 2mm wide, is guided into the fistula. Guide wires are then used to insert a catheter with a special deflated balloon in to the tube, which is then inflated to expand the narrowed segment of vein.

More recently, the Lister-based team has been using a special drug-eluting balloon, which works by inhibiting the growth of cells in one layer of the vein, which leads to narrowing. This approach means that the treatment is likely to last longer, ensuring that patients experience better quality dialysis and longer intervals between such procedures needing to be carried out.

Reflecting on his experiences since April 2016, when he first started dialysing, David continued:

“I attend the Bedford renal dialysis unit three times a week and have done so for over 18 months now. In that time, my fistula has had problems on three occasions – most recently in July of this year. Although I have to go to the Lister, it’s a simple, painless procedure that I know keeps my dialysis on track.

“The team at the local renal unit and their colleagues at the Lister have done a great job looking after me and although dialysis takes up a large chunk of the day – I’m on the machines for four hours every visit – I continue to try and lead as normal a life as possible. The next step will be to have a conversation with the team about whether or not I am suitable to go on the transplant list – but for now, I’m concentrating on keeping well and enjoying family life!”

The 30-minute op that can save diabetes patients from losing a leg - so why aren't more patients being offered this?

The 30-minute op that can save diabetes patients from losing a leg - so why aren't more patients being offered this?

- Last year, Graham Baker, 52, a carer from High Wycombe, Bucks, faced the prospect of losing a leg below the knee, a complication of his type 2 diabetes

- Last September he had a 30-minute procedure called endovascular revascularisation at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford, and his leg was saved

- It involves feeding a wire into the affected artery with a balloon and a stent which squashes the blockage and holds open the artery

Last year, Graham Baker was facing the prospect of losing his left leg below the knee, a complication of his type 2 diabetes.

Poorly controlled blood sugar levels had encouraged the arteries in his left calf to fur up, and this was obstructing the blood flow so much that the tissues and bones in his lower leg were being starved of blood and oxygen.

‘I had a scan to monitor the blood flow in my left leg and was told that without surgical intervention, I would likely lose the lower part of my leg — my years of poor diabetes management had basically blocked up the main artery,’ says 52-year-old Graham, a carer from High Wycombe, Bucks.

But specialists said they could save the leg — and it could be done under local anaesthetic in less than an hour.

It involved a newly refined procedure that clears the artery of blockages. Graham — who is married to Beryl, 53 — had the procedure, called endovascular revascularisation, at the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford last September and his leg was saved.

There are many people in the same position who could also benefit from the procedure, but don’t.

In fact, new figures reveal that one person a day needlessly loses their foot or leg because this simple procedure isn’t more widely available.

Blockages in the blood vessels in the legs (known as peripheral arterial disease) is common, but people with diabetes are particularly prone. This is because nitric oxide, a gas we all produce that helps keep blood vessels healthy, becomes less effective in the presence of repeatedly high blood sugar — as can occur in diabetes.

As a result, the blood vessels are at risk from inflammation; this in turn encourages the build-up of fatty deposits called plaques, which ultimately impede blood flow. While this affects all the body’s blood vessels, the effect is pronounced in the legs because the veins and arteries are longer.

As the blockages can hamper the blood supply, which would normally help with healing, a minor injury to the foot or lower leg can develop into an ulcer and infection, which can spread to the bone. Once there, the infection cannot be treated with antibiotics, meaning amputation is the only option.

Every year there are around 12,000 lower limb amputations in the UK, the majority of which are for people with diabetes.

‘Without adequate blood supply, in diabetics otherwise minor ailments, such as ulcers, can lead to the loss of the foot,’ says Dr Raman Uberoi, a consultant interventional radiologist at the John Radcliffe.

‘Increasing the blood flow even temporarily can help.’

Endovascular revascularisation is a simple way to do that. It involves making a small incision in the groin, then feeding a wire (guided by X-ray) into the affected artery.

A balloon and a stent — a tiny mesh tube similar to the spring in a pen — is inserted over the wire to squash the blockage and hold open the artery.

The stents are often coated with the drug paclitaxel, which helps to prevent the build-up of scar tissue that can lead to re-narrowing of the artery.

The same technique is used for treating blocked arteries in the heart. ‘In a straightforward case, which most are, the process takes only 30 minutes,’ says Dr Philip Haslam, a consultant interventional radiologist at Newcastle Hospitals Foundation Trust.

Data shows the procedure is successful in 85-90 per cent of patients 12 months later.

The technique, recently refined so even small vessels can be cleared, has better outcomes than traditional bypass techniques that involve opening up the leg to remove a vein that is used to bypass the blockage, says Dr Haslam, and studies show that patients who have endovascular revascularisation spend a third less time in hospital and are 12 per cent less likely to need an amputation than those who have a bypass.

So why aren’t more patients being offered this?

The problem, says Dr Haslam, is there simply aren’t enough interventional radiologists — specially trained X-ray doctors — who can perform this type of image-guided surgery.

‘We need to double the trained IR workforce from 433 to nearly 1,000, in order to meet the current demand, never mind the future demand,’ he adds.

‘We need more funding dedicated towards training doctors in this area,’ he explains. ‘Since it’s a quick, cheap, effective and largely painless procedure, this needs to be addressed.’

The procedure is available at most, but not all, major city hospitals. And Dr Uberoi, who is president of the British Society of Interventional Radiology (BSIR), warns that as the number of diabetics in this country — currently four million — continues to rise, ‘the demand for interventional radiology procedures to clear arteries will be even more acute’.

He adds: ‘Crucially, you’re avoiding a whole heap of extremely serious complications further down the line with a quick and painless procedure, with obvious benefits to the patient as well as to the NHS.’

Complications from the procedure are rare, he explains. Occasionally the artery can’t be unblocked because of the degree of plaque build-up.

‘Sometimes the narrowing in the artery can embolise — or break into pieces — as a result of the procedure, and flow off to smaller blood vessels where it can cause further blockages,’ says Dr Uberoi.

‘If the blood vessel is too blocked, open surgery is needed, but that requires longer hospital stays, and carries a greater risk of infection.

‘Compared with endovascular revascularisation, it’s a far from optimal option.’

Nikki Joule, policy manager at Diabetes UK, agrees that people with diabetes need more access to such procedures. ‘Diabetics should have the best possible care and support from a multidisciplinary footcare team who can deliver the best results, including access to specialists who can repair damaged arteries in legs and feet.’

Graham, who’s had type 2 diabetes since the age of 36, had already had a toe amputated in 2013 when in August last year he developed redness and pain in his left foot. Scans revealed that this was due to poor blood flow in the artery supplying it.

He’d also previously suffered an infection in his second toe and the metatarsals — the long bones — in his left foot, and had them surgically removed.

He was surprised at how straightforward the new procedure was. ‘I couldn’t feel it at all, and I was awake throughout.

‘When the surgeon got to the blockage, he inflated a balloon to widen the artery, and the pain in my shin — where the blockage was located — was excruciating for three to four seconds,’ he says.

Graham was out of theatre within 45 minutes. ‘The consultant told me it had been a complete success,’ he says.

He was able to walk that afternoon and was discharged from hospital the next day, and adds: ‘My left leg was saved, and for that I’m eternally grateful.’